ECMAScript 6 a.k.a. ECMAScript 2015 a.k.a. the new version of JavaScript is getting closer and closer to ratification, the current goal is to have the new standard ready in June 2015. This is a big step forward for JavaScript that is becoming a modern language, suitable for all the uses we need.

If you follow tech news you know about some of these changes: classes, modules, spread operators… In this post I will analyze one less known feature: tail call optimization.

CS 101: The Stack Frame

Let’s analyze this simple snippet of code:

function foo() {

console.log("foo");

bar();

console.log("bar called");

}

function bar() {

console.log("bar");

baz();

console.log("baz called");

}

function baz() {

console.log("baz");

console.log("all done");

}

foo();When we invoke foo, a new stack frame is created in memory. A stack frame is

simply a portion of memory where we store some values necessary to execute the

function, for instance local variables, arguments and most importantly the

caller of the function, so when the execution is done the callee can return to

it.

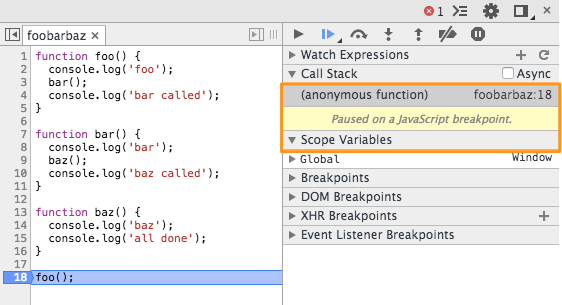

Let’s see this in action using Chrome’s debugger:

In the orange rectangle, you have the stack frame and also a list of local

variables. It’s not exciting but let’s see what happens when we call foo:

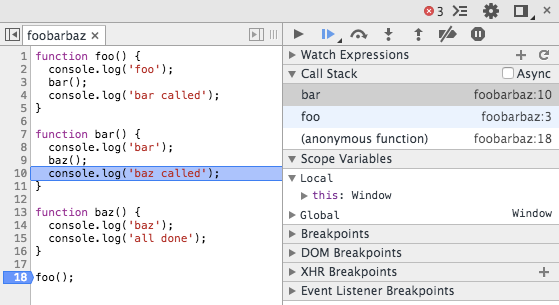

A new stack frame gets created. Notice that the other frame is still there, we

will need it later. After foo calls bar that calls baz, we are in this

situation:

Two new stacks are created, one for bar and one for baz, those stacks are

listed in what is called call stack. The call stack is very useful when you

debug because it tells you the history of your program: which function called

which other function. After baz has done its job it returns back to bar:

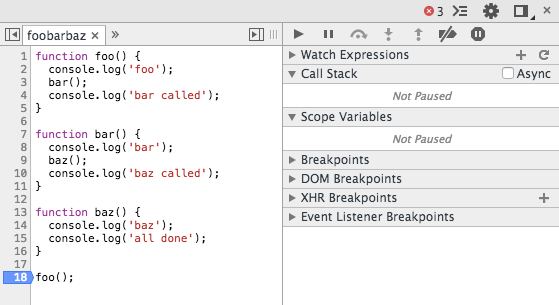

As you can see, the stack frame for baz is deleted because we no longer need

it anymore. Every time a function returns, its stack frame gets deleted. After

our program is done, the call stack will be empty:

Maximum Call Stack Size

Now that you have a general understanding of what stack frame and call stack are, we can see an error you may encounter while programming.

Imagine you have this function:

function foo(n) {

if (n === 0) return;

foo(n - 1);

}If you call foo with a positive integer, it will simply call itself decreasing

the number until it reaches zero. This is how the call stack behaves if we

execute foo(10):

As you can see, 10 stack frames get created until n reaches zero, at which

point the functions begin to return and all the stacks get deleted.

So if n is 10, we have 10 stack frames, if n is 100, we have 100 frames and

so on. What happens if n is 100,000?

As said, every stack frame gets created in memory; unfortunately, a program has a limited amount of memory assigned, so it’s possible that the call stack becomes too big. In this case, we have an error and the program crashes.

Tail Call Optimization

Let’s keep our focus on the previous function. As you can clearly see, the last

thing it does before returning is to call itself. This means that, when the

called function returns, foo will do nothing, just immediately return to its

caller.

This kind of code allows a tail call optimization. With this optimization, if the last thing a function does is to call another function, instead of creating a new stack frame the callee will use the caller function’s frame.

In our case, foo(n-1) will simply use foo(n)’s frame as will foo(n-2) etc.

In the end, foo(0) will simply return directly to the main program instead of

going through the entire call stack.

This is not only faster but it requires far less memory: instead of creating

100,000 frames we simply have 1 that gets re-used. So our call to foo(100000)

will get executed without exceptions.

If you think it’s unlikely you’ll write code like this, think again. Functional programming is rising in popularity and makes heavy use of tail calls. One of the reasons it hasn’t been used too much in JavaScript was exactly the lack of tail call optimization.

Also, many languages are now transpiling to JavaScript. Think of Unreal Engine, which is a C/C++ program, now running in Firefox. Those platforms will benefit from this optimization as it’s already a given for them.

Current Implementations

This is the part where we usually blame IE for not supporting the new cool feature, unfortunately this time we have to blame everyone:

As you can see, only Babel partially supports it. This is of course about to change in the near future.

If you want to learn more about tail call optimization check the ES6 draft.